Indigenous Filipino food sits on the floor between us, cooling in the mountain air. Steam lifts in thin, stubborn threads. A low ring of bowls crowds the woven mat. They sit close, a bit crooked. Some edges are chipped. One bowl has a long straight crack and I think someone meant it to be that way. No, not planned, only worn. The broth smells of ginger. Then something damp, the ground after rain. I lose it before I can name it. Chickens complain somewhere behind the house. A radio mutters from inside, off then on, never quite in tune.

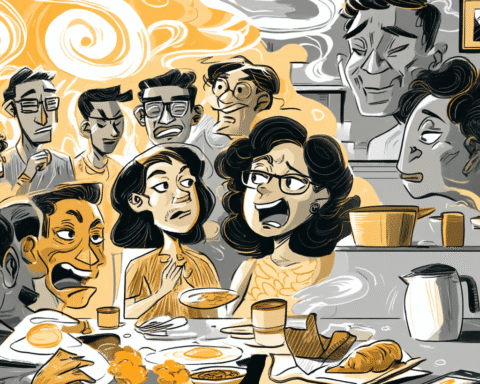

An elder in a faded t’nalak jacket taps the rim of a metal pot with a spoon, soft, almost shy. He says there used to be more. More dishes, more hands, more rules for where each bowl must sit. A feast with a name I fail to catch. I ask him to repeat, he does, slower, yet it still slips past me, too full of soft consonants. He laughs. I laugh, late. This whole meal feels like a story missing one page.

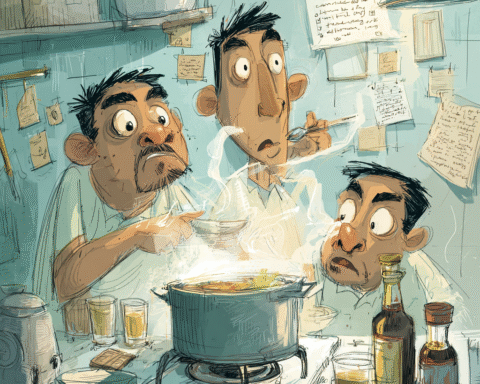

He points to the rice first. Cooked in bamboo, he explains, once, for guests from another hill. Now done in a rice cooker that hums in the corner, close to the outlet, far from the fire. Beside it rests boiled root crops, rough skin half peeled, a chicken stew with floating yellow fat, a slab of pork stiffening as the air cools. Somewhere in earlier years, he says, there would have been rice wine in a shared jar, lip stained by many mouths. Today we drink instant coffee from mismatched cups, a small betrayal no one names. I almost say so, stop myself.

I try to picture the full ritual from his fragments. A pig led in circles, a prayer spoken in Tboli, an elder watching the way blood spreads on packed earth. Food offered to spirits first, then to humans, in careful order. He keeps moving his hands, fingers stacking, a small circle, a lift that stops halfway, like invisible plates sit between his palms. His words go into Tboli, then back to Bisaya, then Tagalog when he remembers I am following slowly. I follow some, lose others. My own language feels blunt here, like a spoon with a warped edge.

He tells me younger ones call this feast old, heavy, hard work. They prefer lechon from town, soft drinks, karaoke. They still gather, he insists, for weddings, for wakes, for days when someone dreams of a bad river and elders grow uneasy. Yet the strict order of dishes, the small rules about which child sits where, these begin to loosen. No one writes them down. I look at the chicken stew, thick with ginger. The surface trembles when someone shifts on the bamboo floor. Memory feels like that surface. Ready to spill, yet also ready to harden.

In tourist brochures, indigenous Filipino food appears in tidy lines. Tboli set menu. Tribal platter. Lake view. Tilapia from the lake, grilled and lacquered with soy, sits beside a mound of yellow rice, a token fern salad, perhaps a small bowl of linaga. Names are short, translated, easy to read from a laminated sheet. The staff smile and speak good Tagalog, slip into English for visitors from Manila or Sydney. On some days, they pose in beaded vests for photos, then change back into T-shirts once cameras go away. I eat the tilapia, taste charcoal and sweetness, and try to match it with the stories from the hill. It does not quite meet.

In the city, far from this house, a restaurant prints the phrase indigenous Filipino food in a careful serif font. Plates arrive on heavy stoneware. There is tinawon heirloom rice from the north, kulitis salad, smoked fish in coconut milk with notes of something wild and green. Servers describe each dish in long English sentences, full of health, heritage, resilience. No tribe is named. No specific hill. No elder whose hand once shook as he salted the broth. The feast becomes pure idea. Also, product. I eat there one evening, months later, and hear my table neighbor say, with deep approval, that it feels so authentic. The word lands on my ear, thick.

As a child in public school, I learned about the Tboli from a social studies textbook. One page. A photo of a woman in t’nalak skirt, brass bells on her waist, a baby on her hip. The caption spoke of weaving, music, farming near Lake Sebu. Food received one brief phrase, something about root crops and rice. No mention of a feast where everyone sits on the floor, where bowls have their own stubborn order. No hint that the meal may hold rules older than the Republic. I grew up thinking of tribes as pictures, not as kitchens. I think about that now, over this steaming broth, feel a small shame catch in my throat.

The elder reaches for the pork, slices thin pieces with a knife sharpened so often it dips in the middle. He gives the first slice to the oldest person present. Not exactly an offering to spirits, he says, though he shrugs as he speaks, eyes sliding sideways in a way that suggests more. He then hands pieces to those with work in the fields, those who wove cloth, those who fished. Children stare, wait, shift, hunger bright in their eyes. The order is loose now, he admits, people rush, they forget. He says the word forget, then corrects himself. No, not forget. Delay. The body remembers even when the tongue fails. That is his claim. Mine, too, perhaps.

Earlier he said the feast is gone. Now he says it sleeps, which argues with his first statement. I do not press him. On this floor, surrounded by bowls, contradiction feels honest. The same family who sells tribal platters to tourists still gathers for wakes with homegrown rice. The same grandson who posts videos of paragliding above Lake Sebu still helps slaughter a pig when elders ask. Indigenous Filipino food lives both on a stoneware plate in Makati and in a dented pot on this hill, and in a rattan basket heading to the fields, wrapped fast, eaten cold. Alive, but thinned.

When I rise from the mat, legs half numb, I try to memorize the scene in useless detail. Placement of the cracked bowl. The way the rice clumps at one corner. The faint sour thread in the broth that I first miss, then find. I tell myself I will remember every part, every gesture, all of it. I will not. Later, writing, I fumble for the Tboli name of the feast and fail again. The gap stays. The meal turns into a shape I feel more than know. Memory feels less like an idea and more like someone sitting quiet in the corner of the kitchen, not yet willing to give the proper name.

In essays and on menus, indigenous Filipino food turns smooth and tidy, presented as pure heritage, nothing awkward left on the plate. On this hill, it sits uneven, half ritual, half convenience, one foot in survival, one in ceremony. The forgotten feast of the Tboli is not fully forgotten, not yet, only scattered into habits and partial stories, into the way a knife moves first toward the eldest, into who receives the bony parts. I leave the house with the taste of ginger and pork fat still on my tongue, and with one steady thought. If no one listens long enough to gather these scattered pieces, the feast will remain present only as a phrase on a menu, a heading in a book, an empty line where a name should stand.