The oil spits when the garlic hits the pan. She leaves it a bit too long and the edges go dark. The smell reaches the street and hangs near the door. People in heavy coats walk past; one or two look in, then move on. Inside, a rice cooker shares the counter with the espresso machine. From the corner, a noontime show from Manila plays on the TV, the voices barely there. On the glass door, a paper sign in plain Arial reads: “Filipino Restaurant. Home cooking.” On lists for “Filipino restaurants Rome,” this place appears as one entry, and the screen says nothing about the life behind the counter.

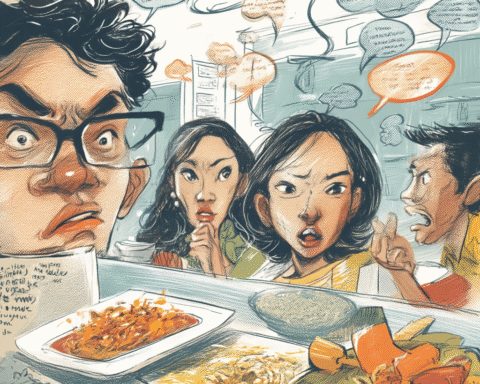

In the narrow kitchen, a woman leans over a pot of sinigang. The broth looks dull, not clear. Her glasses fog up. She sips the broth, thinks for a bit, then adds a small splash of water. The sour edge eases. Less pull on the tongue than in Quezon City or Iloilo. Regulars feel it at once. They ask for extra sabaw in deep bowls and, for some, a small saucer of bottled calamansi concentrate. Italian husbands or co-workers at the next table stay with this softer version. In one of many Filipino restaurants Rome, a single pot tries to answer two sets of taste.

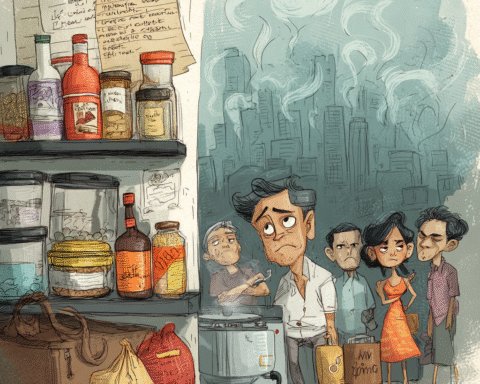

Many cooks in these rooms first arrived in Italy as badante, live-in caregivers in Roman households. They scrubbed another family’s pots, learned supermarket aisles in a language rubbing slowly against the ear, stretched euro coins until the next remittance window opened. In private kitchens under someone else’s roof, they followed local habits. Less salt. Pasta al dente. No rice at night. One legal day off each week, if the employer respected the contract. The rest of the time, they fed others and ate in corners, between tasks, by the sink.

Years later, some of these same women stand in front of their own stoves. Their names sit on business papers as titolare. On the sign outside, the word trattoria or bar anchors them in the Italian street. Among friends they remain ate, older sister, the one who knows what time to line up at the questura, which bus reaches the quartiere, which agency to avoid. The leap from live-in caregiver to kusinera with her own keys looks large on a visa form. Inside the dining room it feels like an old skill stretching into new space. Care work moves from bedroom and sickbed to counter and table.

The menu carries this story in small shifts. There is adobo, though less oil gathers on the plate. Kare-kare arrives in a modest bowl, oxtail trimmed close and peanut sauce a little looser, so Roman diners treat it as stew and sweep bread through it. A plate of pancit canton sits beside a basket of pane instead of extra rice. At lunch, one set menu pairs a Filipino primo and secondo: noodles or boneless sinigang first, fried fish or pork after, a small salad as contorno. Across Filipino restaurants Rome, food speaks as ulam and as course meal at the same time, half turo-turo, half neighborhood trattoria.

Change lives in detail, not in slogans. More vegetables in the pancit because Roman diners look for color and crunch. Less chili in the vinegar because a regular once coughed through his meal and never came back. Turon on a plate with powdered sugar instead of a plain fried roll in brown paper. Each choice, repeated across weeks, turns into a reading of the city. These women know how far to soften a dish without scraping away its center. Years of listening to requests trained them. Salt less. Coffee stronger. Curtains closed. In the restaurant, that same alert ear turns toward taste, mood, and quiet at the table.

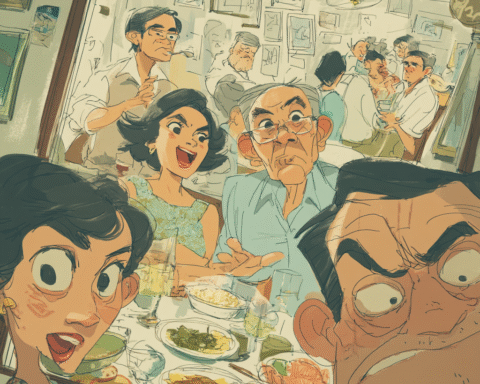

Sunday draws a different crowd. After Mass at a Filipino chaplaincy church, a slow line gathers outside certain doors that online maps tag as Filipino restaurants Rome, almost like tourist spots. Inside, the sound shifts at once. Tagalog rises over the clink of metal spoons on enamel plates. Tired women in sneakers push tables together and hang jackets on chair backs. A child runs between them, speaking Italian to a parent who answers in Bisaya. An older man recites exchange rates from different remittance centers, weighing them out loud. At the counter, shipping flyers lean against a jar of sili labuyo soaking in vinegar.

In these rooms, the restaurant turns into boarding house, remittance corner, and church patio squeezed into one strip of floor. Job leads move from mouth to mouth. News from home lands here before it reaches phone feeds. Stories about employers, kind ones and harsh ones, take shape between spoonfuls of nilaga. A woman who once spent her days inside a stranger’s apartment now presides over a space where others step in on their own terms. She still asks, Kumain ka na? Have you eaten. The tray in her hand, the time on the clock, the rules of the room now respond to her.

The city outside uses its own labels. It calls the place ristorante etnico or cucina internazionale. Landlords often see risk in unfamiliar food, so many of these eateries end up on side streets behind Termini, in periferia near bus depots, under low apartment blocks where rent dips a little. The signboard often hangs over a lottery machine or a coffee counter. The lease once sat under an Italian name. The front part stays a bar for regulars who want espresso or a scratch ticket. In the back, metal trays line up on a heated table. Two rice cookers sit in the corner near a fridge stacked with soft drinks from Manila.

Gender runs through this space in quiet ways. Owners keep earrings off during service, hair tied in a tight knot, aprons worn thin. They handle suppliers, tax forms, and kitchen burns with the same flat tone once used for medication charts and grocery lists. Regulars address them as Tita or by first name. Menu questions and migration questions land in front of them, one after another. Authority in these rooms does not rely on a raised voice. It rests in long recall of who reached Rome in 1998, who needed a bed in 2005, who sent a niece to work in 2010 and slept on a spare mattress near the stockroom.

Food for Italian guests here often travels with a short explanation. A plate of laing appears and someone explains taro leaves, gata, the slow simmer that tames itch on the tongue. An Italian partner tries balut once, face unsure, then picks lumpia and sisig on the next visit. Jars of bagoong stay behind the counter until a familiar voice asks. The owner remembers who enjoys the deeper funk and who leans toward sweet red tocino with garlic rice and a fried egg. Across Filipino restaurants Rome, these small decisions draw a quiet map of how far the flavor of home moves through a foreign city.

For women at the center of this map, success does not glitter. It looks like a second-hand van bought without debt, a daughter in nursing school, a mother’s new roof in Laguna or Samar. Near midnight, the owner sits at a table and sorts small notes and coins. One pile goes to rent. Another to family. Another to the next sack of rice and a box of pork belly. The floor holds the sour trace of vinegar and soap from the mop. Outside, buses pass in bursts, then leave the block to its thin night sounds.

People who type “Filipino restaurants Rome” into their phones usually want directions, a menu, a photo or two of halo-halo in a tall glass. They show up craving lechon kawali or pancit, a flavor remembered from home or one heard about in stories. They leave with full stomachs, then fold back into trains and buses. Work that stays behind lives inside these rooms. In kitchens once closed to them, migrant women learned how Rome eats. In the dining rooms they now run, they teach the city how they eat, under a sign they own, in a language that smells of garlic in cold air.