The broth comes first. A small bowl, cloudy from starch, bright with chopped sili, steam rising in a thin, steady line. The spoon moves and there, almost hidden, the bodies appear. Sinarapan fish swirl like clear commas in the liquid, eyes catching what little light enters the kitchen. Salt, heat, a faint lake smell. On the tongue, the fish break quickly, then leave a light peppery echo that clings to the back of the throat.

For many Bicolanos, that bowl sits near the center of the table. It might be beside laing heavy with coconut, or ginataang tilapia thick and lush. The sinarapan lie in the quiet part of the meal, inside a small cup, yet they mark the meal as place-specific. This is not any freshwater broth. This is Lake Buhi speaking in the smallest voice it has.

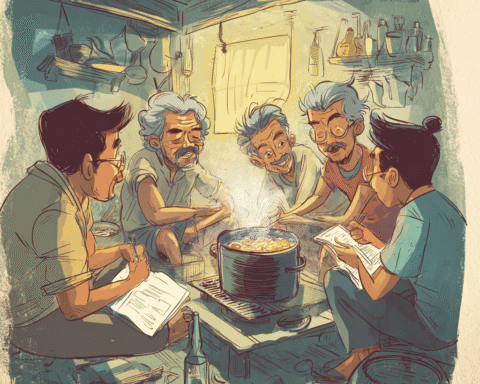

In memory, the story starts at the market. Plastic basins lined in blue, flooded with water from the lake. A vendor lifts a cup and pours it back. The sinarapan pour with it, almost unseen until they move. Children lean close. Adults step aside, already knowing what their hands feel for. Heat, sourness, and lake. That is what goes home in those thin plastic bags.

Old stories say the lake once felt endless. Nets came back heavy. A pocketful of coins bought enough sinarapan for a large pot. The fish filled jars with bagoong-like pastes, sat under the sun on woven mats, and slipped into every kind of ulam. Their bodies were tiny, their reach wide. The fish season not only dishes but also a sense of scale. Flavor lived in the small, not only in slabs of pork or large fish laid across charcoal.

Now the lake feels smaller, even when a person stands at the shore and sees water to the far bank. Fisherfolk return with stories of thinner hauls. The heat in the air lingers longer into the night. Children learn to sleep with electric fans that never rest. Water follows. It warms in shallower layers. It turns murkier, or clears at the wrong time. Quiet changes like this test a species that depends on a precise band of coolness, oxygen, and food.

Scientists speak of rising temperature and acidity. Households speak of strain. The two stories meet in the pot. A catch lighter by a few kilos does not show on a satellite map. It shows in a smaller serving of sinarapan on the table, or in its absence. A parent reaches for the bottle of commercial seasoning instead. The broth still glows red with siling labuyo, yet something underneath falls silent.

In Bicolano cooking, heat often rides on layers. There is the sharp fire of fresh sili, the slow burn of dried, the grounding comfort of coconut milk. The sinarapan sit below these, like a low drum. Their faint bitterness turns the broth into an undercurrent that holds the meal together. Remove that undercurrent and the meal still exists. Rice remains. Coconut remains. But the mouth starts to seek something that no longer arrives.

The loss hides in errands. A lola sends a grandchild to the market for sinarapan, puso ng saging, and sili. The child returns with vegetables, onions, salt, yet no fish. The vendor shrugged. The lake had a rough week. The lola adjusts. She stretches another dish. She says nothing at first. Then she says it twice, at different meals, as if repetition might bend the world. “Mahirap na humanap ng sinarapan ngayon.” Hard to find now.

On paper, the fish gain new labels. Endemic species. Threatened. Indicator of freshwater health. The words sit in reports and proposals. They are important, yet thin compared to the memory of a hand dipping into a basin at dawn. For those who live along the lake, the meaning of sinarapan runs through more ordinary language: pang-ulam, pang–sabaw, pang-bisita. Food for daily life, food for guests, food that signals care.

Climate pressure shifts those meanings. When a foundational ingredient like sinarapan fades, a whole system of flavor begins to tilt. One might adjust a recipe. Add more sukà. Increase the sili. Turn to dried anchovies from another coast. At first, these choices feel minor. Over years, they shape a new palate. Children grow up knowing a Bicol where the base notes come from packets and imported fish, not from something translucent and local.

There is no single day when the loss becomes official. No ceremony for a missing cup of spice. Instead, absence arrives during tasks that feel small: stirring rice into sabaw, packing baon, sharing a late-night bowl with a neighbor. Someone says, “Masarap sana kung may sinarapan.” It would taste better with sinarapan. The sentence trails off. No one argues. The moment passes, then repeats in another house.

The silence around the fish teaches a kind of humility. When the world speaks of climate, it often speaks in grand scales. Degrees. Centimeters. Tonnes. In Lake Buhi, the change sits closer. A grandmother reaches into water and feels fewer bodies brush her wrist. A young fisher spends more hours on the lake for less catch. A cook stands over a pot and decides to save the remaining sinarapan for a special day, then watches those days narrow.

To speak of sinarapan fish is to speak of the thin edge between survival and disappearance. The species holds on while waters warm. People hold on to the recipes that carry its name. Each side responds within its own limits. The fish adjust or fail. The households shift seasonings, portion sizes, expectations. Between these responses sits an uneasy question. When a flavor rooted in place dims, what else drains away with it.

The disappearance of a tiny fish does not break a culture in one blow. People in Bicol still tell stories in kitchens, send remittances, ride jeepneys, pay for mobile load, watch soap operas. Life continues. Yet the loss presses into the cracks of ordinary acts. A bowl of lugaw without sinarapan tastes slightly flatter. A festival table leans more on pork and chicken. The lake turns into scenery rather than pantry.

Every cuisine holds such quiet thresholds. In Bicol, the line might run through a simple bowl where lake water turns to broth and sinarapan flicker like the last visible proof of a relationship between people and a body of water. Once that flicker goes, a cook might still prepare something that looks similar. The recipe title might remain. The mouth knows the difference even when the tongue lacks the right words.

Perhaps the most honest response sits in stubborn practice. A family still buys sinarapan when supply allows, even at a higher price. A younger cook asks a lolo about seasoning, listens to stories about the lake in the seventies, and writes notes on the back of a grocery receipt. In that act, the fish step out of pure resource status and enter story. From there, they move into memory, and from memory into a kind of obligation.

The silent retreat of the sinarapan is not only a story of a failing species. It is also the story of how a cup of spice carries the weight of a place. When the cup empties more often, the question waits at the center of the table, between spoon and bowl. What stays Bicolano once the smallest fish no longer speak in the pot. The answer forms slowly, in kitchens that still listen for a flavor that feels thinner each year.