Typhoon season recipes begin before the wind speaks. Kerosene breath. A pot with a dent. The first metallic sip from the tap, then we seal the drum and stop.

The radio pops. Rice clicks in the tin. I rub a thumb on a packet of tuyo, feel the salt grit, then the bag tears wrong. Fish oil on the fingers. On the shirt. I reach for vinegar. Miss. A small stumble in the dark shelf.

We wait. We wait.

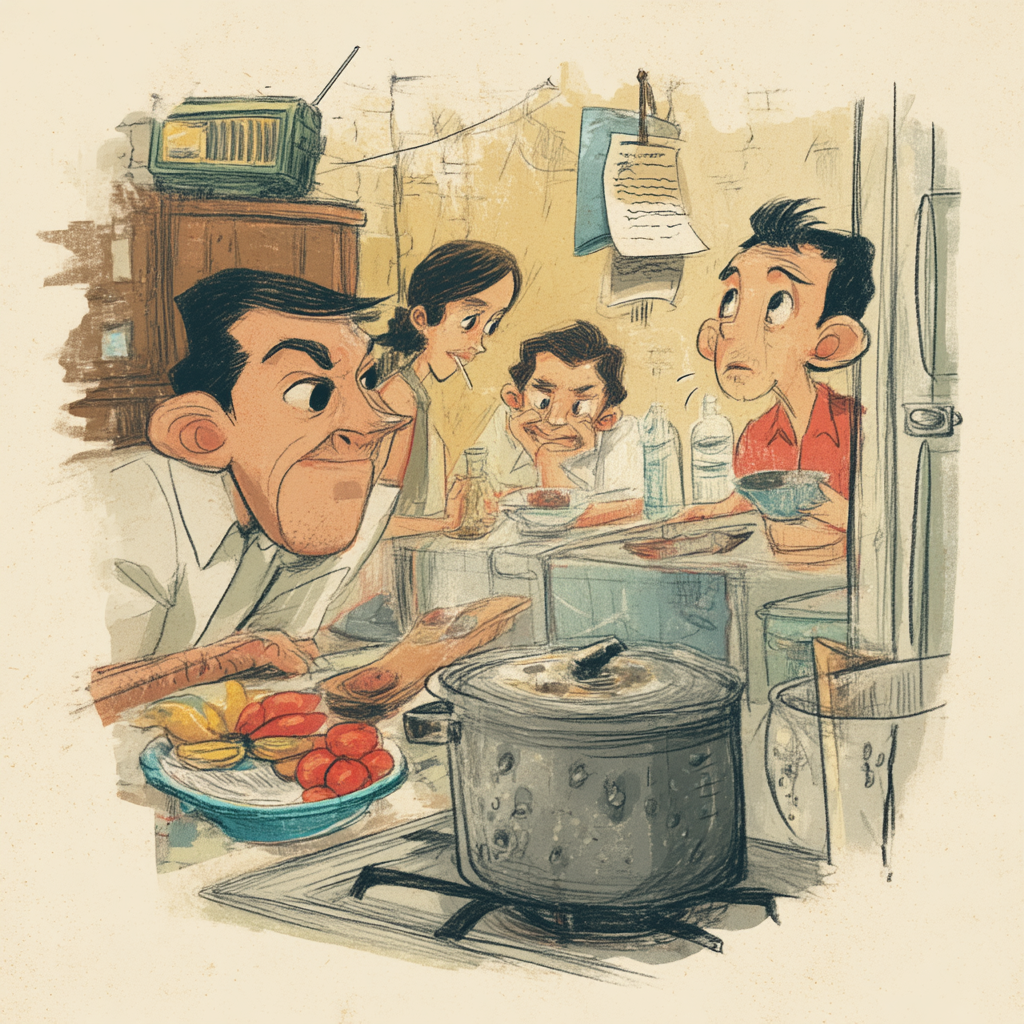

In that cramped kitchen the map of a storm is not on TV. It is on the table. Cans. A coil of saba. Kamote with soil still clinging. An onion that sprouted a green hook overnight, stubborn. I think we had enough rice, but the scoop sounds hollow and I stop

I strike a match. It coughs out. Second try. Flame.

Typhoon season recipes are not written. They are remembered by touch and by guess. Thin the porridge. Stretch the oil. Keep the fire small. I tell myself to plan, but the plan changes with the wind that resumes, then falls quiet, then returns rude.

What cooks here is not only food. What cooks is time. Lugaw leads the line. One cup rice to many cups water, a pinch of salt, a neighbor’s luya sliced thin and kind. Some call it survival food. Then the bowl arrives with steam and a squeeze of calamansi, and the spoon refuses that word. Survival, yes, but also comfort. A contradiction that sits warm on the tongue.

Calamity cooking looks plain, and it is not plain. It asks the pantry a small riddle. What keeps without power. What softens fast. What tastes like home even when the light goes. Malunggay leaves stripped quick from a branch a cousin brought. Tuyo broken into flakes, fried in low oil on a stove that hisses. Onion, garlic, rice. A fast sinangag that smells like morning even at midnight.

I say “we always had sardinas,” then I recall the week the trucks never reached our street. Correction. We often had sardinas. So we learn another path. Galunggong salted hard the day before landfall. A shallow fry. Then a vinegar bath with peppercorns and laurel to keep it longer. Not paksiw exactly. Something between. A family recipe without a name. My aunt put a paper label on the jar once. The ink ran. The jar kept the taste anyway.

In the box of matches a slow lesson hides. Heat is ration. Patience is ration. So you cut small. Boil only what serves many. Kalabasa turns sweet fast when thin. Kangkong gives in with a sigh. Munggo needs time and decision. If the wind grows, save the munggo. If the wind drops, light the longer simmer. I say this like a rule. Then I break it the next storm when the only sure thing is hunger and the child who wants soup now.

My lola kept a ledger of pagkain pang bagyo. Not prices. Proportions. One fist of rice to two bowls water becomes four bowls when a cousin knocks. A wet pencil line shows where she changed her mind. No, more water. No, add luya. She wrote in fragments. She lived in fragments then. We all did.

Typhoon season recipes travel without fanfare. To the sari-sari store for soy. To a neighbor for two saba. To the roof to check the plastic drums. They carry old names into new storms. Arroz caldo that slipped into lugaw when chicken went scarce. Tinola missing papaya but holding on with sayote. No gas. Then charcoal. No charcoal. Then a clay stove borrowed. No stove. Then a ring of rocks in the yard and a pot blackened until the bottom looks like night.

I taste salt, then soap, then no, it is rust kissing the rim of a cup. I still drink. We all do. Someone passes a plate of fried tuyo and cold tomatoes. The oil is sharp. The tomato skin squeaks. The storm steps back a little. Or we do.

Disaster preparedness meals sound technical on paper. In the kitchen they sound like your mother, quick and calm. Boil water first. Save the last propane for rice. Put sugar in coffee for the elders. Wrap the matches. Keep the knife dry. These words live in the mouth. Short. Exact. They outlast the outage. They shape the day, then the night that follows, then the day again.

The lists changed with the years. Powdered milk replaced by gata from a neighbor’s last coconut. Then back again when the tree fell. Canned corned beef traded for dried mushrooms from a balikbayan box that nobody liked at first, then liked. Pantry staples in the Philippines is not a fixed phrase. It bends with income, with distance from market, with whether the bridge holds.

A small radio spits news. A bigger pot answers with a thin sinigang from tamarind candy and fish heads the vendor saved for us and handed over with a shrug. Poor food, someone once said at a party in the city. I said nothing then, and now I cook it again and watch everyone reach for second ladles. Poor, then beloved. A circle that never looks like a circle while you stand inside it.

Typhoon season recipes carry memory like a pocket keeps a coin. Weight that reminds. My father checking flashlight batteries. My mother rinsing rice, the first water cloudy, the second still not clear, the third I forget because someone calls from the gate. A pail sloshes. The floor slick. The dog circles the stove, whining, then sleeping.

We wait. We wait.

There are tricks learned from loss. Hard suman fried in oil to wake it up. Coffee stretched with roasted rice. A spoon of patis to fix a flat pot, then another spoon when taste goes numb after hours of wind. A banana leaf laid over rice for slow steaming on a weak flame. I want to call these hacks. I stop. They are care, not tricks.

People ask how to cook with no power Philippines like it is a single question. I want to answer with a street, a house, a naming of neighbors. With bayanihan as menu. With stoves borrowed and returned. With a bowl passed over a fence, hot. My answer is an unfinished list.

On the morning after, sun at the sink, the kitchen is sticky with smoke and relief. We count what is left. Rice. Two onions. Vinegar. Enough to feed one more. Then two, if we thin and flavor right. I say we are safe. I correct myself. Safe for now. The future stays outside the door, damp and waiting.

Typhoon season recipes move from scarcity to plenty to scarcity again, never in order. They teach thrift. They teach generosity. They show the border where survival becomes culture and where culture, tired and stubborn, refuses to be only survival. The wind quiets. The radio plays a love song that cracks at the chorus. Someone laughs. The pot murmurs. Dinner.