The first image I have of a Filipino mother in our house is not her face. It is her hand, holding a rice spoon, hovering over a plate that is not hers. Steam on her glasses. A towel over one shoulder. Slippers half off her heel, ready to move again. She stands, always stands, while the rest of us learn what it means to sit and eat.

Her plate waits on the counter by the sink. A chipped floral plate, rice already cooling, a single piece of pritong isda placed near the edge as if it might slide off. She moves from stove to sink, stove to table, stove to door. The rhythm feels normal. Ordinary. She refills our soup, wipes a spill, shushes a quarrel. The rice spoon in her hand turns into a baton that runs the whole room. Her own food turns stiff.

In many Filipino households the dining table and the kitchen meet at a narrow doorway. On one side, the seated ones. On the other, the one who moves. Often the Filipino mother stays at that border, leaning against the frame, one hip resting there, never quite crossing. She says, Sige na, kumain na kayo, and laughs off any invitation to sit. A small joke. A small lie. She “already ate.” She insists, busog na ako, even when her stomach answers back.

I once believed she never ate at all. That memory feels wrong on the tongue. I correct myself. She did eat, in fragments. A quick taste of kalyos at the stove to check the salt. A spoon of soup standing beside the pot. The crusty rice from the bottom of the kaldero, scraped and pinched while washing dishes. Hunger spread across hours, never gathered into one full plate in front of her. A meal scattered through the day.

The words we use help keep this pattern steady. Ilaw ng tahanan, we say, the light of the family home. Not boss. Not worker. Light. Gentle and constant, unpaid. When visitors sit at our table, the Filipino mother slips behind them, refilling rice, topping up sabaw, adjusting the electric fan so guests feel the cool air. She laughs when someone tells her to sit. The laugh smooths over the order that keeps her on her feet. It sounds kind. It hides the work.

In that same laugh sits the weight of invisible labor. She plans the menu around everyone else’s taste. The child who refuses ampalaya. The father who wants meat at every meal with his rice and sawsawan. The lola who needs softer food for weak teeth. She tracks who had egg in the morning, who skipped lunch at school, who feels masama ang pakiramdam tonight. No notebook. No app. The ledger sits in her head and in her body. Her back aches while the family grows full.

The cost shows up in small places. In the dark line of varicose veins along her legs. In the way she leans on the counter after washing the last plate. In the habit of saying, Ako na lang, when someone offers help with dishes. She eats last. Often alone. Her rice now cold. The fish reduced to bones and tail. Sometimes the sound comes first. Spoon on plate. A scrape, then another, a bit too fast. Metal catching on porcelain in small, nervous circles, in the corner where one chair still faces the table, long after bodies have moved to the sofa, the TV, rooms down the hall.

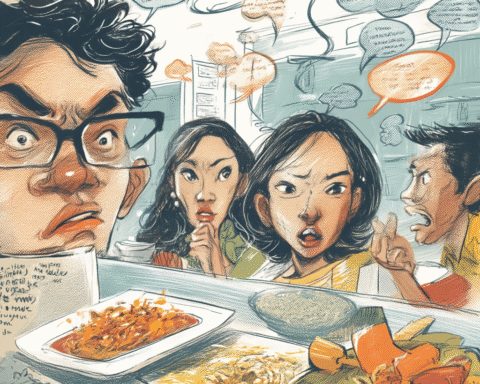

During fiestas the house gets loud. On the table there is pancit in metal pans and kare kare in a dented pot. Chopped pieces of lechon share a tray with a small pile of lumpia and puto. Two plastic pitchers of cold sago gulaman sit near the edge, crowding the plates. The pitchers leave faint wet rings on the cloth. Neighbors stand at the doorway and smell the food. One says, Ang dami naman, then they come in already holding plates. Someone else says, Ang bongga ni nanay, the words pressed out between mouthfuls. The Filipino mother squeezes past them, stove to table to sink. There is oil on her arm. The back of her neck is sweaty. A small strand of hair is stuck there; she leaves it. She stops beside an empty chair and twists the towel between her fingers. Her body leans toward the seat for a second, then she straightens again when the pot on low flame flashes in her mind. Later we flip through photos on a phone. In one she appears as an elbow. In another only the blur of her dress near the frame. Most shots show the food lined up, everyone smiling, her nowhere.

This pattern reaches outside the Philippines. In apartments in Sydney, Dubai, Toronto, California the same scene repeats with different appliances and different brands of soy sauce. The Filipino mother works a shift, rides the train, then steps into the same second shift at home. There are homes where fathers cook now, where sons wash dishes. That sits beside another picture, where many migrant stories still turn around a woman who feeds everyone and eats only when nothing else remains. The kitchen holds both, awkwardly.

Language keeps pace with this labor. We tease mothers who sit down too early. Uy, antamad, someone jokes when she leaves the sink with plates still soaking. We praise the tireless ones. Hindi napapagod si nanay, we say, as if fatigue were a flaw, not a fact. Praise turns into pressure. The ideal Filipino mother holds the house together, serves the food hot, and smiles through the whole thing. When she complains, we flinch. The image shakes. We rush to steady it.

I remember one Sunday when she sat at the table while the rice was still steaming. I tell it as if steam still rose in thick clouds. In reality the top layer of rice had already gone a bit hard. She pulled the chair out with both hands and sat down slow, her knees a little locked. Her face looked unsure, like the seat belonged to someone else. For a moment forks hung in the air and a sentence broke off halfway. Something in my chest pulled tight, off, as if we had missed a cue. Then someone laughed too loud, someone else shifted, spoons scraped plates again, and the room pretended nothing had happened.

Her hand went straight to the serving spoon without thinking. Halfway to the bowl she stopped, wrist hanging there between us and the food. Kayo na, she said, caught herself in the old habit, then set the spoon back on the table with a small, dull thud. The sound felt heavier than the spoon itself.

The taste of that meal blurs now. I want to say the soup leaned sour with sinigang sa kamias. Or it leaned sweet with nilaga. The detail keeps slipping away. What stays sharp instead is the scrape of her chair on the floor, the sound of her weight resting on four legs of wood, not on her own tired legs. A plain sound. Also rare. It marked a shift no one named out loud.

To speak of the woman who never sat down to eat is to speak of how a Filipino household trains itself. It trains daughters to serve first. Sons learn to expect a full plate. Elders come to measure love in refills of rice. This training looks gentle. It arrives first as extra ulam on your plate, as a mother saying, Sa iyo na yan, and pulling her hand back. Your mouth fills before you answer. It feels like love, of course it is love, and by the time you notice anything else, the shape of it has already settled under your skin. It is also structure. Unequal. Gendered. Hard to unlearn.

If someone begins to notice this, the story tilts a little. A child grows older, lifts a pot, learns to fry fish without flinching at the oil. A partner clears the table before reaching for a phone. A family waits until the Filipino mother sits, really sits, before anyone picks up a spoon. These acts look small from the outside. They interrupt years of habit. Change enters the kitchen quietly, one refused refill, one shared plate, one seat pulled out from the table and held until she takes it, or until she hesitates and walks away again.

The woman who never sat down to eat was never only one woman. She turns up in many homes, in different provinces, across time. People praise her, copy her, defend her, then worry about her. She is also tired. When she finally sits, we do not erase the past years of standing. We feel them in our bones and in the food that used to reach our plates while her own meal cooled beyond repair. Someone passes her the bowl first. Someone else watches her chew and does not say anything wise. The chairs stay where they are, slightly uneven around the table, while she finishes what is on her plate.