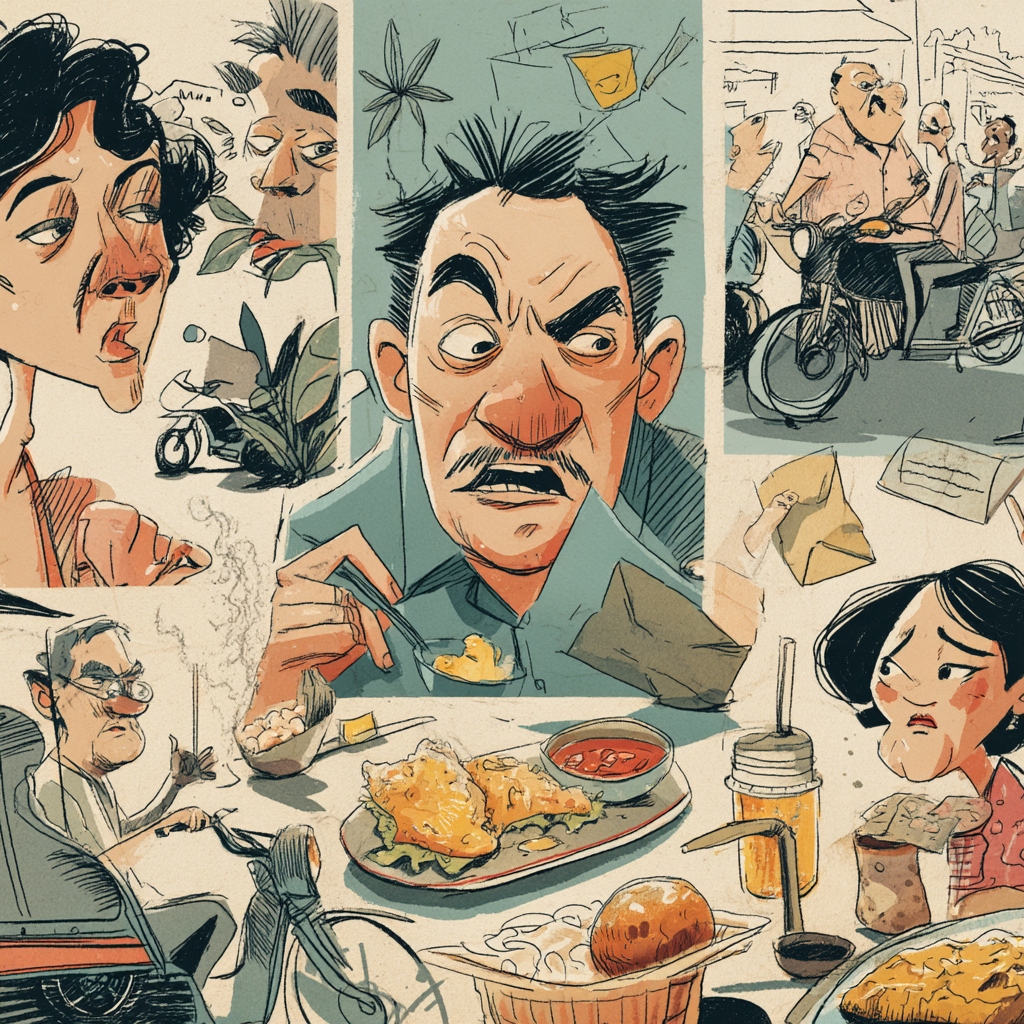

Delivery riders lean on scooters outside a carinderia. Plastic helmets sweat. The smell is… is vinegar and diesel. A bell rings from an app. No one looks up. A pot of sinigang breathes, thin steam. I hear spoons tap enamel bowls. Or maybe it is coins.

I buy tokwa’t baboy in a paper tub. The vinegar bites first, then quiets. A rider asks for extra sawsawan and rice, says he will eat later. He pockets the two extra suka packets anyway. Pocketed for whom. For when.

The phone glow is cold on brown hands. Names slide past. Units. Orders. He is dispatched north, then west, then north again. A loop that does not end so much as fray.

We used to wait in lines. We used to wait at tables. I think of the old padyak driver who hauled us through flood, wet slippers, lugaw in a covered bowl. Different vehicle, same labor. I am wrong. No, not the same. The map has changed.

On the curb, sauce drips onto asphalt like little, dark commas. I wipe my finger on a thin napkin. Too thin. A dog noses the spill. I step back and almost say salamat, then stop. Who am I thanking. For what.

I remember the first time my mother sent me to buy pancit bihon on credit. The owner wrote our name in blue pencil on the wall. We ate with apology and pleasure. Debt had a face. Now the delivery riders arrive at the gate and the debt is buried in the app, in a service fee with a name that sounds clean.

Food delivery rewrites distance. Shortens it for some. Stretches it for others. The condo elevator opens into cooled air, a guard nods, a signature or a selfie, then a door that barely opens. A hand takes the paper bag. The smell stays outside.

The riders form a moving kitchen line. They do not stir, but they move heat. They do not plate, but they carry memory. On the back of a bike, laing crosses a river, pares crosses a bridge, halo-halo shivers under plastic wrap and still somehow melts. It will arrive and be photographed, tagged, then eaten while watching something else. A good life. But wait.

Who eats. Who serves. Who waits, and who watches. The categories spill. A rider who once worked as a cook waits to eat his own lunch at 3 p.m., lukewarm. A condo resident who once delivered pizza as a student tips in exact change, apologizes. He remembers. He forgets.

Hunger looks different in the city now. Not only empty stomachs. Also long gaps between bites. The delay that becomes habit. The snack that becomes dinner. Urban hunger wears uniforms and lanyards. It has a schedule. The new geography is traced by surge hours and penalty zones, by areas where elevators are slow, by gates that never let you in, only up to the lobby and no further.

A rider at the red light peels a banana. Peel into a crumpled plastic bag, then into his jacket. He catches me looking. He tilts the bag, half a smile. “Para hindi matapon,” he says. Green. He goes. Quiet work. Quiet hunger.

We say convenience, but we mean distance. We say contactless, but we mean faceless. We say platform economy, but we also mean new gatekeepers, new tolls. Old hierarchies dressed in push alerts. A home kitchen is now a dispatch point, a restaurant a storage hub. The delivery riders sit between them like a hinge that creaks.

I watch a boy in slippers carry two bags for his older cousin. No app account, no name on the screen, but the work is the same. They split the fare at the end of the night. Or they intend to. It is late. They argue. I look away and pretend to read a receipt. The words jump. The numbers blur.

There is also the rider who eats first. He opens the order and takes one fry, then stops. He seals it again. He looks around, ashamed of a small hunger, smaller than the company’s fees, smaller than the weather. It is wrong, he says. Then he shrugs. Contradiction lives with appetite. A code of conduct meets a growl.

Once, food on the street told you the neighborhood. Kwek-kwek meant students nearby. Pares pointed to jeepney terminals. Today, the street tells you where delivery riders can rest, where shade gathers, which security guards allow them to sit. These are the new plazas. The asphalt canteen. The curb cafeteria.

My aunt keeps a Tupperware of cold adobo near the gate. She used to offer water to basureros. Now she offers one spoonful to delivery riders. “Kahit tikim.” Even a taste. A small repair. She calls it charity and then corrects herself. No. Courtesy. She looks at me as if to ask if it matters. I say yes. Then I am not sure.

We talk about safety. Helmets, reflectors, wet roads. We forget food safety on a motorbike under noon. A plastic lid sweats into fish sauce. Lettuce wilts into the fried chicken’s heat. Some dishes travel well. Adobo always forgiving. Sinigang not so. Inihaw na liempo tends to cool into silence, fat clamping down. Still ordered, still in demand.

There is a rhythm to arrivals. My neighbor orders lugaw whenever a meeting runs long. Another asks for suman on Sundays, as if to bring the province into the city, even if loosened, even if sweetened past recall. I am guilty of this, too. I order kakanin to taste my grandmother’s hands and taste plastic instead. The memory fails. Or maybe I fail it.

A friend, rider before, now dispatching from a cramped room, says the city hums at 8 p.m. “Sabay-sabay,” then he glances at two screens, pinches the bridge of his nose, forgets to finish the thought. Work pulls him away.

A guard tells a rider to move along. No motorcycles by the entrance. The rider rolls two meters forward. The guard looks satisfied. Nothing changed, yet something did. It often feels like this. The map redrawn by a gesture so small it barely counts. Until it does.

I open my tub of tokwa’t baboy again. The tofu has drunk the vinegar. It tastes deeper now, louder. I want to save some for later. I eat it cold. A scooter coughs to life. Another rider arrives, checks his phone, looks for the right tower. The names on his screen pile up. Some are nicknames. Some are companies. One is a number. He frowns. Shakes his head. A small breath, almost a laugh, then he turns.

The city teaches a new home economics. Portioning attention. Pricing time. Counting steps between lobby and elevator like calories. We pay delivery fees to buy back minutes we traded away earlier. We eat at the screen and call it rest. When the food arrives, it brings another story with it, not only from the kitchen but from the road, from all the pauses, all the small refusals, the napkin that tears, the helmet that fogs, the missed bite that will become dinner.

Later tonight I will see delivery riders bunched under a tarp by a closed panaderia. They will be laughing. Someone will be sipping sago’t gulaman too fast and coughing. A sensory stumble, a joke, an apology, more laughter. A phone will buzz and one of them will say “O, ikaw na.” Your turn. He will stand, stretch, and for a second look like a boy waiting to play. Then the visor drops. He is gone before the rain decides.

The carinderia closes. The city keeps eating. The maps update without ceremony. Somewhere, a mother packs two extra suka packets into a pocket. For whom. For when. The hunger moves, and we follow, late to name it, earlier to taste it, trying to learn better from the delivery riders who draw the routes we refuse to see.