The plate arrives quiet, white, almost bare. In the middle is a small piece of pork, seared on one side, its fat still soft. Beside it, a pale green streak of sauce smells of coconut and sili. The heat of gata and siling labuyo reaches you before the fork does. A crumble of something browned and salty clings to the edge, like bagoong that spent time near smoke. On top, thin leaves of kangkong and a shard of crisp pork skin cross each other as if unsure where they belong. You taste, and there is Bicol, there is Ilocos, there is a city dining room already calling this modern Filipino cuisine.

The servers offer short explanations. “Pork in a Bicolano-style sauce, with Ilocano bagnet, served as a plated main.” The words sound neat. On the tongue, the story moves in another order. Heat from the sauce arrives first, gata sweet and rich at the back of the mouth. Salt from the fried pork hits next, familiar from pinakbet or an afternoon of bagnet with rice and tomato. Greens follow last, quiet but insistent, like a side dish from home refusing to stay at the edge of the plate. The dish behaves like a sentence built from words in different neighborhoods, then asks your palate to read.

For years, restaurant talk liked the word “fusion.” Filipino with French. Filipino with Japanese. Adobo in pasta, kare kare inside a burger. The promise spoke of travel on a plate. In small kitchens in Manila, Quezon City, Cebu, and Davao, another direction gathers strength. Chefs turn inward. They look at the map of the archipelago and begin to read it not as separate specialties, but as a box of shared vocabulary. Plates appear where a Bicolano way with coconut meets an Ilocano comfort with preserved and fried meats, where sourness from the Visayas leans into smoke from the Cordilleras.

This is still modern Filipino cuisine, only its grammar works differently. The reference point shifts from foreign neighbors toward cousins from other regions. On one plate, laing no longer arrives in its full, familiar form. The sauce once wrapped around taro leaves becomes a thin, elegant pool under grilled fish from Zamboanga waters. Beside it stands a small dome of tinapa rice, a memory from coastal breakfasts pressed into shape with a ring mold. One spoonful touches all three, and the bite reads like a new sentence built from old words.

Earlier generations met other regions through travel or through relatives who brought food as pasalubong. A jar of fish paste from the north tucked into a suitcase. Pili nuts wrapped in plastic from a cousin in Bicol. Cassava from Leyte arriving days later than planned. The taste of elsewhere entered the home kitchen in small, stubborn ways, mixed into ongoing pots of sinigang or fried with garlic without ceremony. In chef-driven dining rooms, those migrations of taste now move in plain sight, under warm lights, on tasting menus stretched across several courses.

On these plates, structure matters inside this modern Filipino cuisine movement. One chef might start with a foundation of starch signaling a region, like pinipig from the north toasted into a brittle base. Another might treat acidity as the subject of the sentence, drawing from the sharpness of batwan in Negros and a gentle tang of suka from Sorsogon. A fragment of longganisa rests beside a smear of coconut vinegar reduction, the two flavors echoing each other in a short, sharp phrase. Diners learn to follow the sequence: salt, heat, smoke, sour, crunch. It feels like learning a new syntax, where each regional note keeps its accent yet joins a shared conversation.

Language on menus tries to catch this grammar in motion. Lines describe laing “rethought,” pinakbet “deconstructed,” sawsawan “elevated.” Under those words lies something older: the habit of making do with ingredients able to travel, the comfort with substitution, taste memory that recognizes kinship among dishes built far apart. A plate pairing Vigan longganisa crumbs with coconut cream from Quezon may sound new in the dining room, yet in city homes families have long mixed groceries from different provinces inside one pot, especially in streets where neighbors hail from many regions.

The new plates differ less in idea than in discipline. Proportion receives close attention. One spoonful of sauce instead of a bowl. Two cubes of root crop instead of a heaping serving. Heat kept in check so the taster still notices the small, bitter edge of malunggay leaf or the faint sweetness of grilled onion. Plating follows a quiet order, drawing the eye from bright to brown, from leaf to meat. Each element serves a role in the sentence the chef invites the diner to read. A drizzle of patis jelly no longer hides in the background. It steps forward as punctuation.

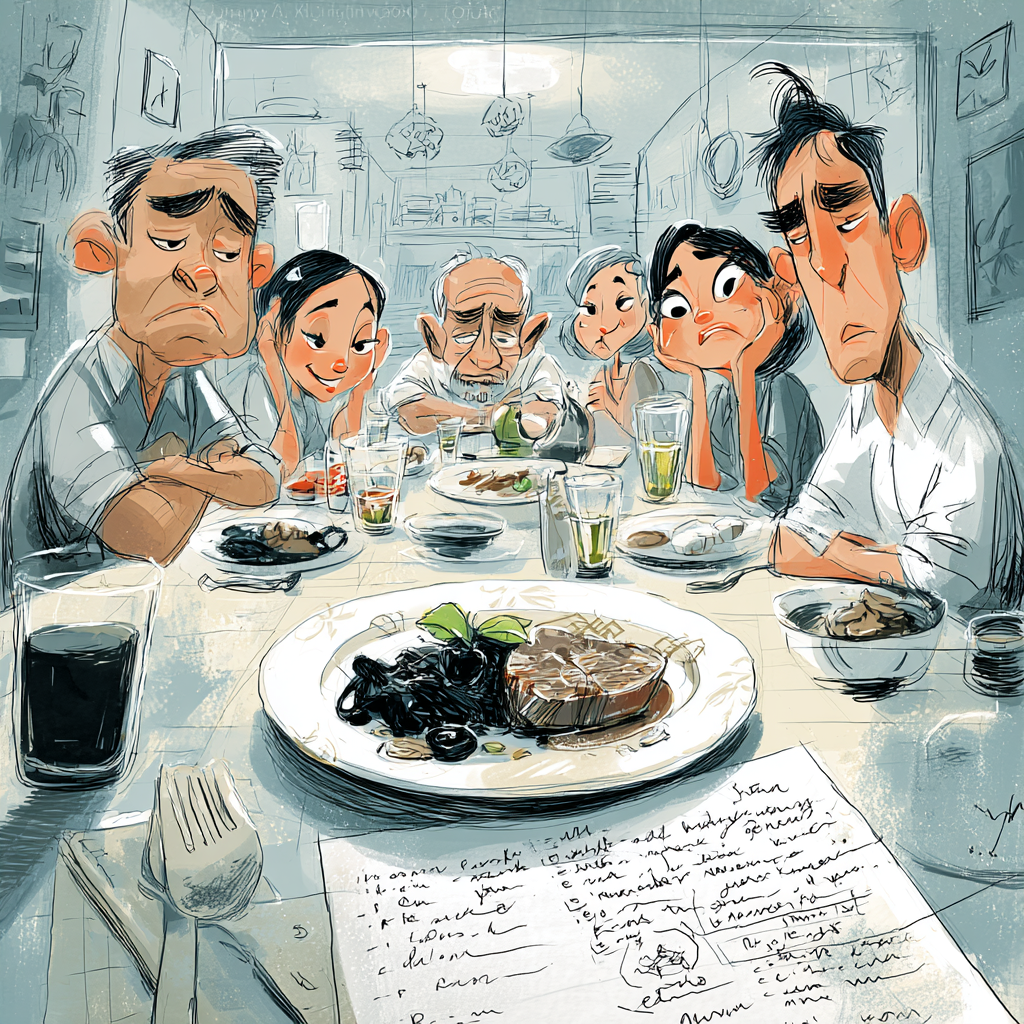

For diners, this grammar of regional recombination asks for a slightly different posture. You look closer. You listen to the server and to your own memory. You search for the Bicol in the coconut, the Ilocos in the crunch, the Visayas in the sour edge that lingers. When recognition arrives, it brings a small tug, a private link to a grandparent, a childhood trip, a province visited during school break. When recognition fails to arrive, curiosity turns toward regions whose flavors now share space on your plate.

Tensions sit inside this movement. Some plates risk turning regional names into ornaments, adding “Bicol” or “Ilocos” on a menu line for color while using little of each region’s logic. Others smooth strong tastes in favor of clean lines and gentle flavors that fit a tasting menu more than a fiesta table. The more polished the plate, the easier it becomes to overlook long routes of ingredient and labor behind those flavors.

At its best, this new grammar of modern Filipino cuisine gives shape to an older story of movement. The archipelago has long held porous shores, open to both trade and migration. Workers left Bicol for the city and carried kinunot in memory. Ilocano traders brought bagoong far from home. Cebuano seafarers brought back stories and strange spices, then slipped those new flavors into stews at home. Today, younger chefs plate those journeys on porcelain, laying things out so one bite follows another in a clear, steady line.

You step out of the restaurant and the street carries the smell of more ordinary dinners. Fried fish, boiling sinigang, barbecue smoke from a stand on the corner. At home, you stir coconut milk into a pot with dried fish from a northern province shop, without second thought. On the table, the dish looks plain. On the tongue, regions meet. In that small, everyday crossing, the grammar of modern Filipino cuisine keeps writing itself, quietly, one plate at a time.