Tausug cuisine sits on the tongue like tide. A sip of broth, smoke clinging, pepper biting soft, then sharp. Hands tear bread. Steam fogs the plate. Salt and wind. Salt and wind.

A cook taps a pestle against a chipped bowl. Palapa hisses in hot oil. Garlic catches first, I think, or maybe the scallion greens. No, the shallot. The air goes sweet, then stings. The flame flutters as if the monsoon had slipped in from the Sulu Archipelago and found the stove.

I remember the first time I tasted tiyula itum. Black as low tide rock. Meat clean, almost medicinal. The char of burnt coconut took me somewhere older than the kitchen. Or I wanted it to. I was wrong at first. Not clove. It was cassia bark. A sensory stumble, corrected by the slow honesty of the bowl.

We say trade made the islands rich. Then we taste lunch and see the other ledger. Routes in the mouth. Names in the stockpot. A map hiding under the stew. Or not hiding at all.

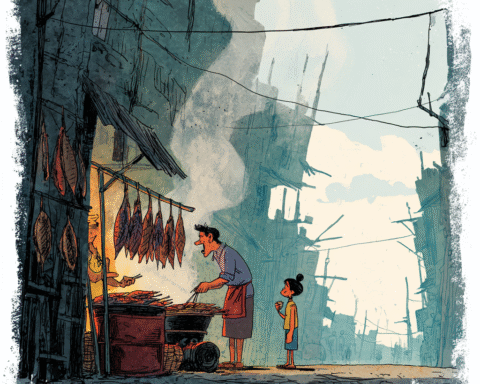

The sea is the pantry. That is an easy line. Too easy. Still true, yet incomplete. Fishermen bring tuna that smells like steel and rain. The market shouts early, then goes quiet as boats leave again. Geography is not just place. It is pace. It is hunger that waits on weather and wakes before light. I keep thinking of the old Sultanate of Sulu, how treaties and tribute felt far away yet tasted close, in small things like a clove tucked into rice, a strip of dried fish glossed with oil.

Spice did not arrive with fanfare. It arrived tucked inside stories and cargo, in the pockets of traders who swapped rumor with nutmeg. Palapa was already ready to meet it. The pounding of sakurab, chilies, ginger. A rhythm that says make do, then make more. The paste folds into eggs, into fish, into the everyday. Not ceremony. Habit. Then again, habit becomes ceremony when a child asks for seconds and someone smiles without looking up.

Here is the contradiction. People say Tausug cuisine is fiery. Then the broth is gentle, and it is the smoke that steals up behind you. Heat stands back. Aroma walks ahead. The spice trade made bold promises. The pot answers softly. A hush that lingers. A quiet bite.

I keep hearing the sea while chopping. The board thuds like oars against a banca. I add onions, then stop. Too many. I scrape a few aside. Self-correction is part of the recipe, even when no recipe is written. Salt, then wait. Taste, then wait again. There is a patience baked into these islands that does not show off. Water meets fire. Wind cools the pot. A small adjustment and the dish returns to itself.

To talk about the spice trade is to talk about the patience of distance. Nutmeg from the North Moluccas. Pepper passing from one palm to another, losing names and gaining uses. Someone calls it by an Arabic word on Monday, a Malay word on Friday, a Tausug word at the table. The archipelago keeps these shifts like a ledger of flavor. Not an archive in a museum sense. An archive that gets eaten and rewritten daily.

In tiyula itum, burnt coconut turns to itim, the color of depth. The fire leans into the pan until the flakes go from brown to near bitter. Stop short of ash. Add water and watch the black bloom. It looks severe. It drinks light. Yet the broth is steady, not harsh. You expect swagger from something so dark. You get restraint instead. Geography turned to flavor, not ornament. Again, soft answers to loud routes.

Travelers describe the Sulu Sea like a road. Wide, uncertain, then suddenly clear. I think of a rice pot set to simmer while someone mends a net. I think of a child dipping their finger into palapa, then flinching, then returning for more. Repeated mischief. Repeated learning. The same motion again tomorrow. And the next day. This is how routes become muscle memory.

Markets in Jolo pile chilies like small volcanoes. Dried fish hangs as if wind had frozen mid-breath. A vendor slices lime over grilled squid, the juice spitting, then calming as it soaks. You hear three languages in one price negotiation. Four, if you count the finger tap on the scale. Spices here do not sit in glass jars. They sit in gestures. They move as you move. The archive breathes because the people do.

Some say history sits in palaces. Another version says it sleeps in treaties. I prefer the kitchen version. A pot scraped with a wooden spoon that someone’s uncle carved. A knife that has seen too much coconut. The steady clatter at dusk when the boats ease back in. A thin radio song. A cough outside the door. The way palapa keeps the oil colored even after the fire is off. I wanted to call this technique. It might be that. It might also be habit, accident, and the slow education of appetite.

Tausug cuisine is often described through meat and heat. Yet there is a careful brightness tucked inside. Lime, green and thin-skinned. Young coconut water lending a shy sweetness to a stew that otherwise looks stern. The islands learned to hold both. Salt and sour. Smoke and perfume. A repetition that becomes a signature. Salt and wind. Salt and wind.

I try to write a clean history of these routes and keep tripping over lunch. The neat line refuses me. A fragment here. A spice there. Someone says their grandmother did it differently and I believe them. Of course she did. Water boils at her pace. Wind changes on her shore. The recipe is correct until it is not. Then corrected again.

What remains, after the boats leave and the plates are stacked, is a small clarity. Tausug cuisine keeps the sea close without bragging. It lets pepper talk, but not shout. It burns coconut until the edge, then steps back. It welcomes what the traders carried, then teaches the newcomers to sit down and behave. The archipelago as archive is not a theory. It is a table where the routes arrive, steam a little, and taste like they have always belonged. Or almost. The tongue finishes the paperwork. The memory signs, sometimes messily, sometimes not at all